The fall of Assad marks a new era for Syria under Ahmed al-Sharaa, with shifting alliances abroad and daunting challenges at home.

In December 2010, Mohammed Bouazizi, a young fruit and vegetable vendor, set himself on fire in front of the City Hall of the little-known town of Sidi Boudiz in Tunisia, in protest against the abuses of the local authorities toward his business. Bouazizi died a few weeks later in the hospital. Still, his act unleashed a powerful movement against the regime of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, who would eventually flee the country. The uprising of the Tunisian people gave momentum to a wave of pro-democracy protests across North Africa and the Middle East, soon to be known as the Arab Spring, leading to the fall of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Muammar al-Gaddafi in Libya.

In Syria, however, the situation was initially relatively calm. Since 1971, first Hafez al-Assad and, from 2000 onwards, his son Bashar, had ruled a one-party police state that crushed dissent, controlled politics through a secret police in the best Orwellian style, and sustained its economy through drug exports. This iron grip over the population began to crack after several teenagers were arrested for graffiti inspired by the Arab Spring that called for revolution. The incident sparked mass demonstrations demanding the release of thousands of political prisoners who had been held captive by the regime for decades. Assad did not yield an inch to the protests, and his troops brutally repressed the population, provoking the near-unanimous rejection of the international community and the formation of an insurgency against the regime, developments that would ultimately trigger a civil war lasting almost fourteen years.

By mid-2015, the regime was in its most fragile position. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, al-Assad controlled only 26% of the country; he had lost the Idlib region to al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate, Jabhat al-Nusra, while the historic city of Palmyra had fallen to the Islamic State, whose meteoric rise posed a grave threat to his survival in the conflict.

At this point, Vladimir Putin decided to support his historic ally (the Russian Federation has maintained bases in Syria since Soviet times) and intervened directly in the conflict. Russian airstrikes targeted the Islamic State and multiple rebel factions, while on the ground operated Iranian-backed advisers and militias, including Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shia group allied with Tehran. The Damascus–Tehran–Moscow axis regained the initiative and, after a sustained offensive, the regime reconquered key areas such as the city of Aleppo. Russia’s intervention, together with the Iranian and Hezbollah deployment and the use of Wagner Group mercenaries, decisively altered the balance of the conflict

The Islamic State’s influence began to wane from 2016 onwards as attacks by the Syrian army and its allies, as well as by the United States and Kurdish militias, gradually weakened it. In October 2019, Donald Trump announced the death of the group’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, in a nationally televised speech following a raid carried out by U.S. Special Forces. In this way, the United States declared victory over the Islamic State and announced its intention to withdraw its military presence in Syria over the coming years, once the remaining pockets of resistance were eliminated.

In the northeast of the country, Kurdish presence was consolidated. The Syrian Democratic Forces (the Kurdish forces) established a de facto self-government east of the Euphrates River, controlling even Raqqa, the former capital of the territory once dominated by the Islamic State. However, most of the territory under their administration, although vast, was desert, and the country’s main cities remained in al-Assad’s hands.

Following the ceasefire reached in March 2020, the front essentially froze. Bashar al-Assad controlled 65% of the country’s territory, including Damascus and Aleppo. In the northwest, an opposition enclave persisted in Idlib province, dominated by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), heir to Jabhat al-Nusra, while east of the Euphrates the Kurdish administration linked to the Syrian Democratic Forces remained in place. At the same time, several Arab states adopted a more pragmatic stance toward al-Assad, and in 2023 Syria was readmitted into the Arab League after a twelve-year absence. Even Turkey opened the door to resuming dialogue despite years of hostility.

In November 2024, HTS, led by Abu Mohammad al-Jolani launched a lightning offensive from Idlib that captured the city of Aleppo and, in less than two weeks, defeated the Syrian army across the country, forcing al-Assad to flee to Russia. The triumphant entry of al-Jolani into Damascus, received as a hero by the local population, would mark the end of the civil war that had plagued Syria since 2011, opening the way to an uncertain political and regional scenario.

Who is the leader of the movement?

Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, or Ahmed al-Sharaa, using his civil name, has risen as the new President of the Syrian Arab Republic after the victory in the Syrian Civil War by the group HTS, which he led. He was born in Saudi Arabia into a middle-class Syrian family. His family returned to Syria when he was around eight years old, and his life unfolded normally until he became radicalized as a consequence of his perception of the events of the Second Intifada in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Upon reaching adulthood, he traveled to Iraq in 2003 to join al-Qaeda and fight the U.S. Army during the invasion that year. He was captured by American forces and imprisoned in Iraq until 2011. Almost immediately after his release, al-Jolani obtained a high-ranking position in al-Qaeda in Iraq under its new leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, with whom he had shared imprisonment. Al-Baghdadi sent al-Jolani to form al-Qaeda’s armed branch in Syria, which gave rise to al-Nusra.

During its first years of existence, al-Nusra was known for exercising brutal violence against minorities such as Christians and Alawites. Its methods resembled those of other al-Qaeda affiliates, and it was accused of acts such as beheadings of prisoners and attacks on civilians. Al-Jolani’s stance was more pragmatic than that of other jihadist leaders, and it was common for him to seek alliances with other opposition forces against the regime. Ideologically opposed to al-Baghdadi and his aspirations to globalize jihad, al-Jolani maintained a more national focus on Syria, more patriotic, and rejected both the idea of forming a regional caliphate and carrying out attacks in other countries.

When al-Baghdadi created ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) in 2013 to operate autonomously in both countries, he attempted to absorb al-Nusra, which al-Jolani refused. This provoked a conflict between the two organizations, which was resolved by al-Zawahiri (supreme leader of al-Qaeda after Osama bin Laden) in al-Jolani’s favor, ordering al-Baghdadi to continue operating only in Iraq. This led to ISIS’s split from al-Qaeda and the rupture of relations between the two terrorist groups, which from then on became enemies.

In 2016, al-Jolani renamed al-Nusra, creating the organization Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, in order to completely break away from al-Qaeda and reform its image, focusing solely on the Syrian conflict. Shortly afterward, in January 2017, he absorbed other Islamist groups from the Idlib region and formed Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Since then, al-Jolani has moderated his positions and has been known for reflecting a more tolerant Islamist approach in Idlib, the region he de facto controlled, focused on overthrowing the al-Assad regime. In 2021, he declared that HTS would implement Sharia law, “but not according to the standards of ISIS, or even Saudi Arabia.”

Governance and foreign projection after the fall of the regime

The Assad regime was characterized by a long trajectory of repression, cruelty, and systematic violations of human rights. The survival of this Alawite family dynasty, which, despite representing a demographic minority, managed to monopolize the structures of state power, can be understood, in part, by the sustained support of a solid core of strategic allies.

The most decisive actor was Iran, which, for many years, not only provided financing and weapons but also deployed its proxies (Shia militias such as the Iraqi or Afghan groups) to reinforce the Syrian army, integrating thousands of foreign fighters. This strategy had a dual objective: to keep Syria within the “Axis of Resistance” against Israel and the United States, and to secure a strategic corridor from Tehran to Lebanon.

Hezbollah, as an actor subordinate to Tehran, also played a fundamental role. It intervened directly in crucial battles such as those of Qusayr and Aleppo. However, after numerous Israeli bombings and the killings of several of its leaders, including Hassan Nasrallah, the Lebanese group has been left severely weakened.

This new situation has been accentuated by the arrival to power of the HTS administration under the leadership of Ahmed al-Sharaa (al-Jolani), which has brought about a drastic change in the relationship between Syria and Iran. Unlike the Assad regime, which openly depended on Iranian support, the new government has restricted Tehran’s influence on all fronts. The Revolutionary Guard and the Iraqi Shia militias no longer have carte blanche on Syrian territory, and their military presence has been limited. Moreover, Hezbollah can no longer use Syrian territory as a logistical hub to supply its arsenal.

The new government has begun to strengthen ties with Turkey, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, distancing itself from Iran’s regional agendas and pointing toward a more pragmatic foreign policy to restore national sovereignty and cease to act as a satellite state of Iran.

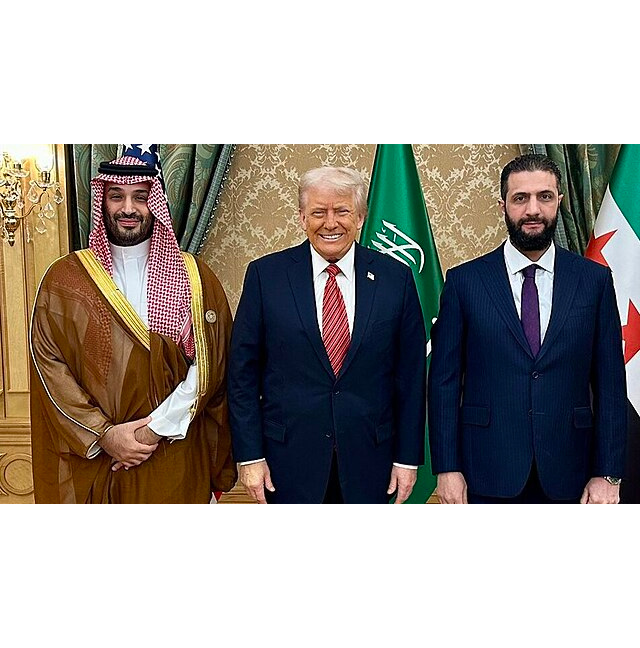

Al-Sharaa’s first official trip was to Saudi Arabia, where he sealed an agenda of cooperation in energy, technology, and health with Mohammed bin Salman. Shortly afterward, he visited Turkey at the invitation of Erdogan, with whom he agreed to transform the bilateral relationship into a “deep strategic cooperation.”

This regional shift was consolidated with the backing of the United States, which lifted all sanctions through General License 25, opening the door to investments and economic relations. The European Union followed suit days later, although it conditioned the lifting of sanctions on respect for human rights and an inclusive policy toward all minorities. Despite reservations about his past, al-Sharaa has managed to weave a network of key support that distances Syria from the Iranian orbit and repositions the country in regional and international diplomacy.

The regime change has also had a significant impact on Russia’s role in Syria. During the Civil War, Russia played a crucial role in the survival of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, intervening militarily in 2015 to prevent its collapse. That intervention consolidated Russian influence in the Eastern Mediterranean, strengthened its alliance with Iran, and allowed Moscow to position itself as a central actor in the Middle East. Russia facilitated operations by the Syrian regime that were widely denounced as war crimes, while using the humanitarian crisis as part of its regional repositioning strategy.

After al-Assad’s flight to Moscow in December 2024, the Kremlin claimed to have achieved its objectives in Syria. Today, although it no longer acts as the main supporter of the old regime, it maintains its embassy and the military bases of Tartus and Khmeimim (Latakia). The Syrian army still depends on Russian weaponry. In addition, Moscow has cultivated an image as a “protector of minorities,” as evidenced by its response to the massacre of Alawites in March 2025, when it received more than 8,000 displaced persons.

Rebuilding order: political, military, and social challenges in post-Assad Syria

Since the fall of al-Assad, the new government of al-Sharaa has sought to consolidate power and rebuild state authority, but the stabilization of Syria remains a complex challenge. By dissolving all the structures of the previous regime, including the security forces, a vacuum has been created that still does not seem to be fully resolved.

In March, a constitutional declaration was enacted to guide the transition, and a new cabinet was formed with representation from minorities: Alawite, Christian, Ismaili, Kurdish, and Druze, as well as technocrats who had served as ministers in al-Assad’s governments before the civil war. However, real power remains concentrated in al-Sharaa’s inner circle, particularly in key ministries.

On October 5, Syria will hold elections to choose a new People’s Assembly, the first parliament since the fall of al-Assad. The government aims to rebuild institutions and gain international legitimacy to stabilize a country devastated by war. One-third of the 210 seats in the assembly will be directly appointed by President Ahmed al-Sharaa.

In terms of security, the lack of effective control over the new armed forces has been a constant source of instability. The massacre of approximately 1,200 Alawites in March, following attacks by pro-Assad militias on the coast, exposed the internal fractures of the new system: groups supposedly integrated into the army acted independently, without a unified command. Added to this is the economic precariousness, which hinders the payment of state salaries and pushes many fighters to depend on clientelist structures or informal sources of income, thus increasing the risk of them becoming destabilizing elements or insurgents.

Moreover, sectarian tensions remain active. In recent months, several incidents between Druze and pro-government militias have resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Druze in Suweida province, highlighting how quickly local tensions can escalate into large-scale violence.

At the same time, external pressure worsens the situation. Israel, concerned about the Islamist drift of the new regime, has intensified its offensive with airstrikes, such as those carried out in July near the presidential palace, and with the occupation of Syrian territory. In recent weeks, both countries have come close to agreeing on the general outlines of a possible deal, after several months of talks mediated by the United States. However, certain obstacles still keep the two sides from reaching an agreement, such as Israel’s demand to open a land corridor to Sweida, which Syria considers a violation of its sovereignty.

Difficulties and hopes in Syria’s reconstruction

After a decade of conflict and destruction that caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and the exodus of millions of Syrian refugees to Europe, the rebellion that began back in 2011 as a consequence of the Arab Spring revolutionary movement seemed doomed to failure. The initial popular hope quickly vanished under the brutal repression with which al-Assad responded to the protests, unleashing a bloody civil war and the suffering of his people.

More than a decade later, when Syria’s conflict seemed to have faded into the background for the major Western powers, who had indirectly accepted the Assad dynasty as the “lesser evil” destined to rule indefinitely, HTS, led by al-Sharaa, managed to take Damascus in less than two weeks, seizing on the moment of weakness of the strategic partners that had kept al-Assad in power, Iran and Russia.

However, it is not certain that the fall of the regime will bring a lasting solution to Syria’s deep structural problems. The economic situation is devastating: according to the United Nations, more than 90% of the population lives below the poverty line, one-third of housing has been destroyed, and public services are almost nonexistent.

Although al-Sharaa presents himself as pragmatic and tolerant, uncertainty and a degree of skepticism persist in the West, which does not forget his past in al-Qaeda and will closely scrutinize the evolution of his government.

On September 24, al-Sharaa took a major step toward rapprochement with the West by delivering a speech at the United Nations General Assembly in New York, something no senior Syrian leader had done since 1967. In his address, he defended the management of his de facto government and called for sanctions relief as well as financial assistance from the United States and the European Union, which appear willing to collaborate with the Syrian leader as long as human rights are respected and minorities in the country are protected.

Preventing the weight of the recent past from keeping the country from taking off and achieving the peace its battered people deserve is Syria’s formidable challenge. The international community should place this goal above any strategic interest of the parties involved.

REFERENCES

- Al Jazeera. (2025, February 2). Syria’s President Al-Sharaa meets Saudi Arabia’s MBS in first foreign trip. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/2/2/syrias-president-al-sharaa-meets-saudi-arabias-mbs-in-first-foreign-trip

- Borshchevskaya, A. (2025, June 5). Russia’s strategy toward post-Assad Syria. The Washington Institute. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/russias-strategy-toward-post-assad-syria

- CONFLICTED. (2024, December 4). The Syrian Civil War Reignites [Podcast episode]. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/episode/1vxxKmtyMq1Jt7fAfT3pZa?si=8a5643166a3b4a15

- El Orden Mundial. (2025, January 16). La guerra de Siria: parte 1 [Episodio de pódcast]. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/episode/546giDSioyWMcOzgIdjLYr

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025, September 22). Arab Spring. In Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Arab-Spring

- Esaá, E. (2025, May 21). La Unión Europea levanta las sanciones a Siria, pero con condiciones. France 24. https://www.france24.com/es/medio-oriente/20250520-la-uni%C3%B3n-europea-levanta-las-sanciones-a-siria-pero-con-condiciones

- FRONTLINE PBS | Official. (2025, July 2). Syria After Assad (full documentary) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXVAjOt17NQ

- International Crisis Group. (2025, May 22). A helping hand for post-Assad Syria. https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/east-mediterranean-mena/syria/helping-hand-post-assad-syria

- Kings and Generals. (2025, March 9). Syrian Civil War SUMMARIZED – Kings and Generals [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lkyTdaP0J-0

- MacFarquhar, N. (2024, December 8). The Assad Family’s Legacy Is One of Savage Oppression. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/08/world/middleeast/assad-family-legacy-syria.html

- Moreh, D. (Director). (2022). The corridors of power [Documentary]. Showtime Documentary Films.

- Schenker, D. (2025, March 11). Enough with the hand-wringing: Al-Sharaa is better than Assad. The Washington Institute. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/enough-hand-wringing-al-sharaa-better-assad

- Schenker, D. (2025, June 5). After Assad: The future of Syria. The Washington Institute. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/after-assad-future-syria

- Tunakan, B. (2025, May 24). President Erdogan met with Syrian interim leader Al-Sharaa in Istanbul. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2025/05/24/president-erdogan-met-with-syrian-interim-leader-al-sharaa-in-istanbul